Issues in the ostrich skin and feather supply chain

Needless violence against these great birds is little known, and considered luxurious.

Ostriches are wild animals native to parts of Africa. Here – living alongside zebras, giraffes and other animals – they spend over seven hours each day on the move, running nearly 70km per hour.

Despite this, ostriches are confined to controlled farms and feedlots for fashion.

The history of ostrich farming

Ostrich farming began in the second half of the 1800s in South Africa, where the bulk of the industry remains today. The industry exists primarily to profit from the sale of ostrich feathers and skins, which are sold to the fashion industry.

Today, ostrich farming takes place across many parts of the world, including in climates unnatural to ostriches. Ostrich farming occurs across parts of Africa, the United States, Europe, and Australia.

In ostrich farms, native vegetation is often denied to birds, who are instead fed lucerne in a controlled system designed for commercial value, rather than their well-being.

Ostrich farms prioritise profit over wellbeing

Farming codes of practice in areas including South Africa and Australia include no requirements for ostriches over six months old to be provided shelter from the elements – not even in the form of trees. This may mean reduced costs for the industry, but puts ostriches at risk during extremely hot days, storms and so on.

Ostrich-keepers have also been recorded stating they only became interested in the line of work when they ‘realised [they] could produce a lot of birds, in a small area’. This ignores the great need ostriches have to run far and wide.

Perhaps most shockingly, in Canada and the United States, no developed codes of practice exist at all, showing no regard for the welbeing of ostriches.

The way that ostriches are confined and kept on farms often results in psychological distress.

These mighty birds have been documented on South African farms repetitively biting the air, chewing at wire fences, and displaying other common signs of psychological distress.

Ostrich feathers are increasingly being used in place of fur and as

fluffy embellishments considered ‘cruelty-free’.

This couldn’t be less true.

Live-plucking

Ostriches do not have a moulting season, and so their feathers are either plucked or cut off. With such little transparency in the industry, which is unregulated in some countries, there is little way to be sure of the most common method of feather collection.

While live plucking is forbidden in many areas where ostriches are farmed, undercover investigations of the industry have documented routine live plucking of birds in South Africa, where most feathers used in the fashion industry are sourced.

Feather cutting

When feathers are legally collected before ostriches are slaughtered, they are cut off just above the feather’s bloodline. Only some feathers are able to be obtained through this method, with the remaining feathers only able to be collected after slaughter. Bags are placed over the heads of the ostriches that are having their feathers cut off.

Image: PETA

Brands selling both ostrich feathers and skins buy into a slaughtering supply chain.

Ostriches can live for up to 40 years in their natural habitat, but are slaughtered at ~12 months old.

Image: PETA

Some ostriches are transported to slaughterhouses, others are killed on farms.

On farm slaughter

It is common for ostriches in South Africa to be killed on-farm, as shown through extensive and ongoing investigations – critical to understanding an industry that is so secretive. Some such investigations have taken place on farms providing skins to Hermès and Prada.

Other birds watch on as distressed birds have a bag placed over their head, are confined, killed and butchered.

Image: PETA

Killing in slaughterhouses

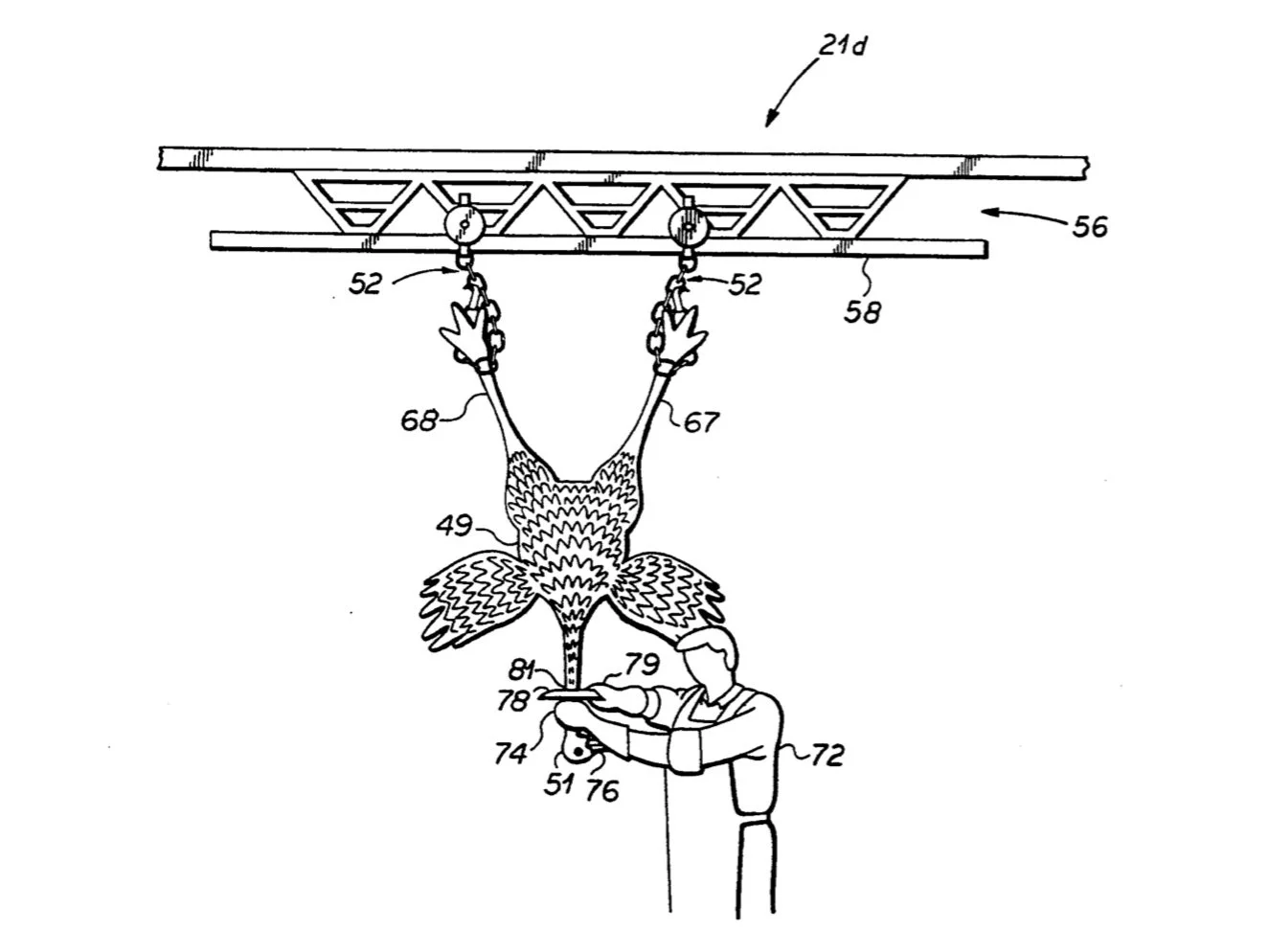

Before ostriches are slaughtered for their skins to be sold, tanned and made into handbags, while their feathers are used in other accessories and garments, they can be denied food for 24 hours, under Australian and South African codes of practice. When ostriches are killed in slaughterhouses they are stunned – either with a captive bolt gun or electrically – before being shackled and hung upside down, and then bled out.

Image: diagram for an ostrich slaughter method patent.

People who work in slaughterhouses can develop mental health issues like perpetration-induced stress disorder, due to the traumatic and violent nature of their work.

Many slaughterhouse workers are marginalised and societally disadvantaged individuals, as no one with other options really chooses to kill for a living. These workers are more at risk of developing mental health issues considered by Yale Global Health Review as ‘psychological consequences of the act of killing’.

If we wouldn’t be able to cope with slaughtering sentient animals ourselves, why pay someone else to?

Image: An ostrich who is about to be hung up on shackles, slaughtered for fashion // PETA

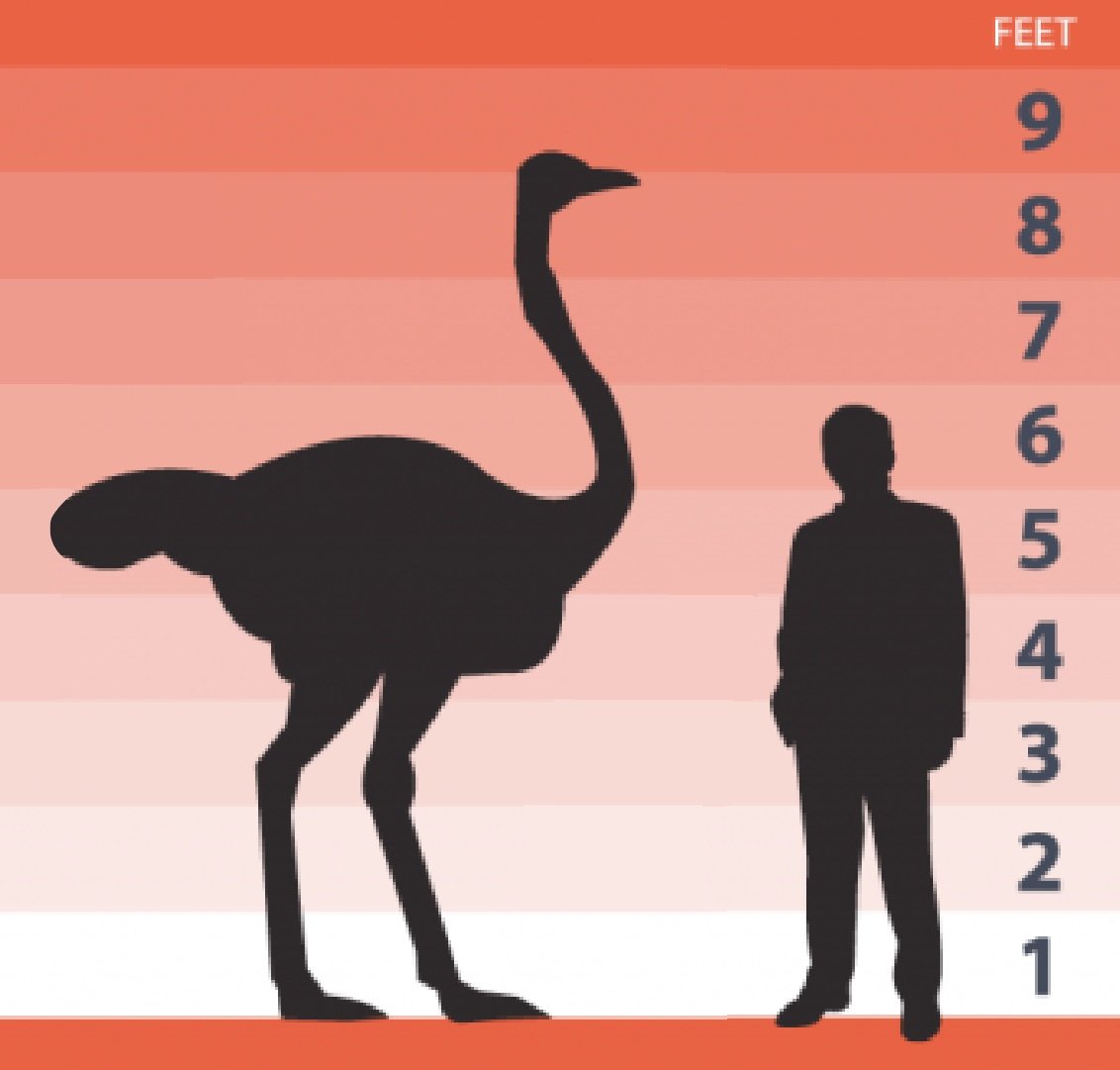

Ostriches are very large animals, with a will to live just like any other species – humans included.

It’s not surprising then, that humans working in roles that involve farming, exploiting and killing ostriches can be at risk of injury by these enormous animals. Slaughterhouse workers face high levels of physical injury.

Meanwhile, people working on ostrich farms are at risk of serious injury if they are kicked by ostriches. Prevention methods are put in place to avoid lacerations and other serious injuries caused by an ostrich and their strong kick, should they correctly identify humans working on farms as dangers to them.

To prevent human cuts, as well as lowered profits in skin sales due to scars, it is common for ostriches to have their toes trimmed. This ‘trimming’ is a partial toe amputation for birds, often resulting in heavy bleeding, and in some cases, chronic pain when walking.

Image: Altered PBS infographic (removed other ratites from feet scale)

While ostriches suffer and are slaughtered, also impacting humans, the environment is harmed by ostrich farming, too.

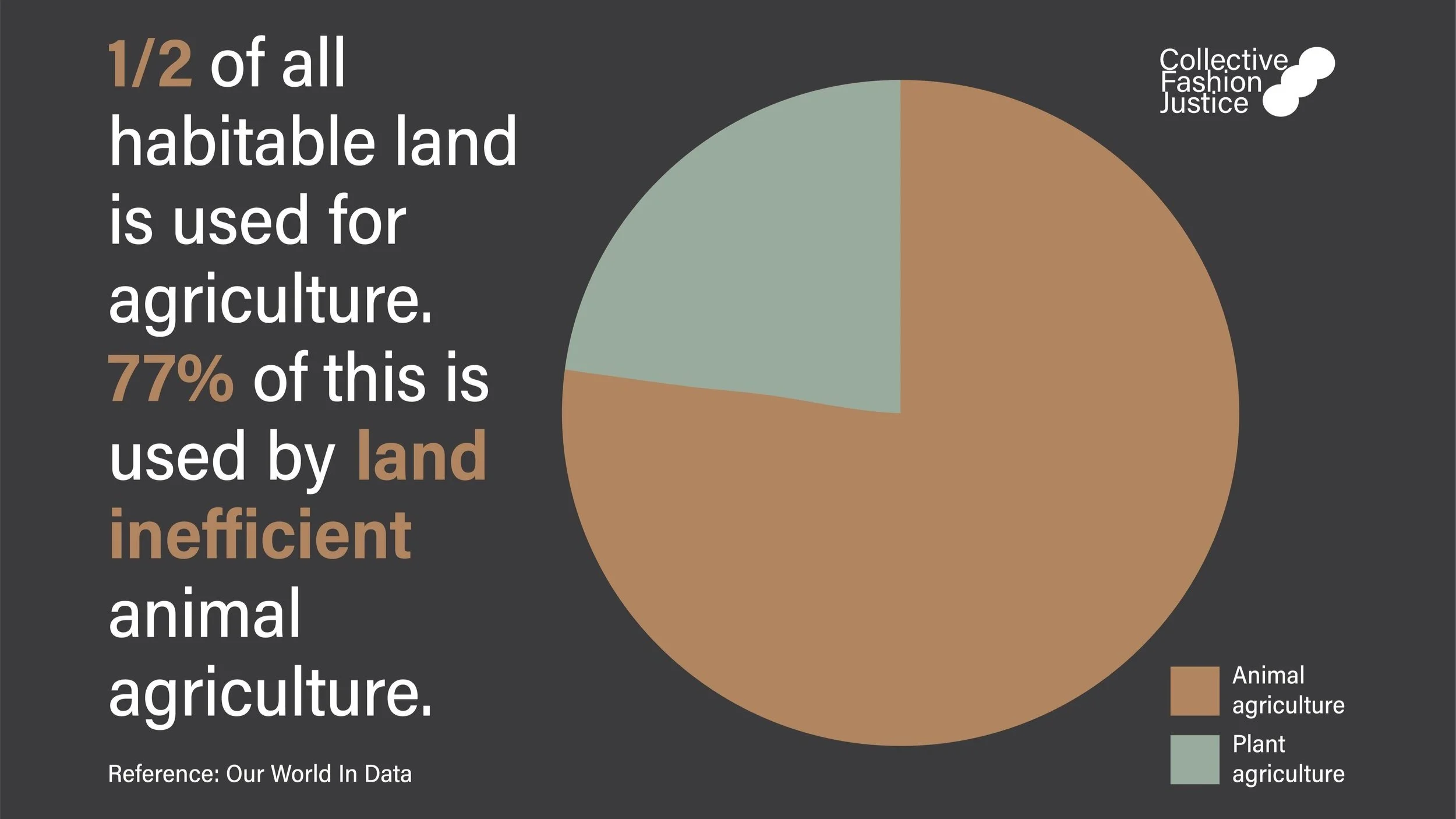

Inefficient agricultural land use

Whenever animals are bred and reared for production in modern agricultural systems, rather than plants, land is being used inefficiently.

Half of all habitable land – so forget glaciers and barren land – is used for agriculture. Of this land, 77% is used for raising animals for slaughter and growing crops to feed these animals.

When we feed animals in order to turn their bodies into ‘products’, more land is used to produce their feed than would be required if we used land to directly feed and clothe ourselves. Efficient use of land is critical to protecting precious biodiversity.

Eutrophication

As with factory-farms rearing ducks and geese for down, nitrogen is released in the waste from ostrich farms.

This waste – made up of urine, faeces, parts of dead birds, broken eggs, feathers and other organic matter – can lead to eutrophication if it is not properly disposed of.

Eutrophication is the over-enrichment of waterways, which can result in dead-zones where aquatic life cannot survive. There are not enough systems in place to prevent eutrophication caused by nitrogen flow off of feedlots packed full of ostriches.

Slaughterhouses and waste

Slaughterhouses which kill ostriches are not designed so differently to any other.

Slaughterhouses are extremely water intensive and they often pollute surrounding waterways. Slaughterhouse pollution is full of blood and other bodily fluids from organs and so on.

If water is not properly treated, it can cause eutrophication, soil contamination impacting soil fertility, and biodiversity loss. It can even harm the health of surrounding communities.

Image: Blood fills a river near a slaughterhouse after a leak // Daily Mail

The future of fashion recognises wild animals and their environment as worth protecting, not as exploitable objects.

Want to keep learning?

-

Our report on the feather industry

Feathers are the New Fur: Cruelty in Disguise is our report on decorative feathers and the ethical and environmental implications of their use.

-

Down industry

Down is never ethical. It is either ripped from live birds or their carcasses. These animals are sensitive and sentient, but are victims of violence for profit.

-

Cruelty is out of fashion report

An overview of the fashion industry’s laws and policies on wild animal products, from Collective Fashion Justice and World Animal Protection.